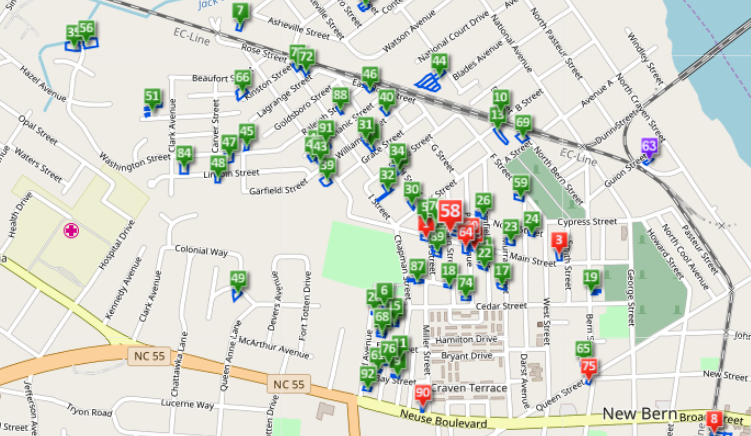

Photo: The city has a lot of properties for sale: 92 are listed on the city’s website. Of those, more than 70 are located in the Greater Duffyfield area. (City of New Bern map)

It’s an unrelenting list of failed dreams: Greater Duffyfield homes and buildings in disrepair, ordered torn down by the city and later sold off at dimes on the dollar.

It’s a tragedy on a personal scale for the families who are losing their properties, but in the broader picture, it’s costing taxpayers money — a lot of it.

Just this week, buildings facing city-ordered demolition were put to votes by the Board of Aldermen for 1127 H Street, 725-727 West Street, and 1607-09 Dillahunt Street.

At the same meeting, vacant lots where houses were ordered razed by the city were sold at foreclosure auctions in which there was just one bidder: 1111 Williams St. and 1112 Grace St. (adjacent lots sold separately to the same person).

All five properties are located in the Greater Duffyfield section of New Bern, a predominantly African-American neighborhood. In fact, more than three-quarters of the city’s surplus properties are in that part of New Bern, virtually all of which were obtained through foreclosures.

Aldermen breezed through the four of the five in rapid succession on Tuesday, save for no-votes by aldermen Sabrina Bengel and Bobby Aster, who have raised concerns that the city’s process for selling surplus property is costing the city money and misses opportunities for better options.

But the voting process stalled entirely on the fifth and final property. More on that in a bit.

The demolition order is just the midway point. If the city later sells one of these properties, it is the culmination of a years-long process that started when a declining building first came to the city’s attention.

The same process was used on a much larger scale with the former Days Hotel at Five Points, which was razed summer of 2017 under city order.

The city fronts the money for the demolition, placing liens on the properties until the bills are paid, which is often never. In those cases, the city forecloses and then lists the properties for sale.

Then it waits for bids of at least 25 percent of the tax value of the property. If bids come in, the city advertises for upset bids. The high bids are often far less than the tax value of the properties, and fall far short of paying the city’s and county’s expenses.

The process can take years, and the city has a lot of properties for sale: 92 are listed on the city’s website.

The problem is two-fold: One, the minimum bid of 25 percent does not take into account how much local government has spent on the property or back taxes. Two, many of these properties aren’t even worth the tax value.

Take 725-727 West St., for example. The building there came to the city’s attention following a complaint filed in June 2010. A warning letter was sent by certified and regular mail to the owner a month later. A fire further damaged the building in June 2012. A minimum housing hearing was held in April 2013, and the owners were given a year to complete necessary improvements. Six months later a building permit was issued, but work was never completed.

On Tuesday, seven years and eight months after the building at 725-727 West St. got bad enough for the city to get involved, the Board of Aldermen ordered the building to be razed.

A quote to demolish the house, hand-scrawled onto paper “by PW,” came to $6,500 and includes asbestos removal.

The Craven County tax office puts the value of the double-lot property with improvements at $81,530. Tax value of the bare land is $14,440. Zillow, an online service that estimates the real estate values, thinks the property is worth about $102,000.

But judging from recent cases, the city and county won’t come close to getting that kind of money if 725-727 West Street ever comes up for sale.

Take 1111 Williams St., for example. A derelict house was once there, torn down by order of the city. A lien was put on the property and the city eventually foreclosed. At the time of foreclosure, taxes were due amounting to $3,850.42 owed to the county and $3,726.69 owed to the city, a total of $7,577.11.

Back taxes aside, the city paid $3,200 to demolish the house, the city and county paid $2,273.83 in foreclosure costs, and the city paid $205 to advertise for an upset bid.

In short, the county values the property at $4,000. The city and the county put $5,678.83 into it. On Tuesday, the Board of Aldermen agreed to sell the property for $1,000.

Loss after expenses: $4,678.83. Lost property taxes: $7,577.11. Total loss to taxpayers: $12,255.94.

That’s just one property. There are 91 more to go, more than 60 of which are in the Greater Duffyfield area.

How the city sells surplus property has been put on hold by the Board of Aldermen until a better process can be devised. The surplus property sold on Tuesday came in under the wire.

How these properties fall into this situation varies but generally are because of neglect by absentee owners, or neglect by homeowners unable or unwilling to pay for needed repairs.

Often, the cost to bring some of these houses back to minimum standards exceeds the value of the house once the work is done. In short, it doesn’t pencil out.

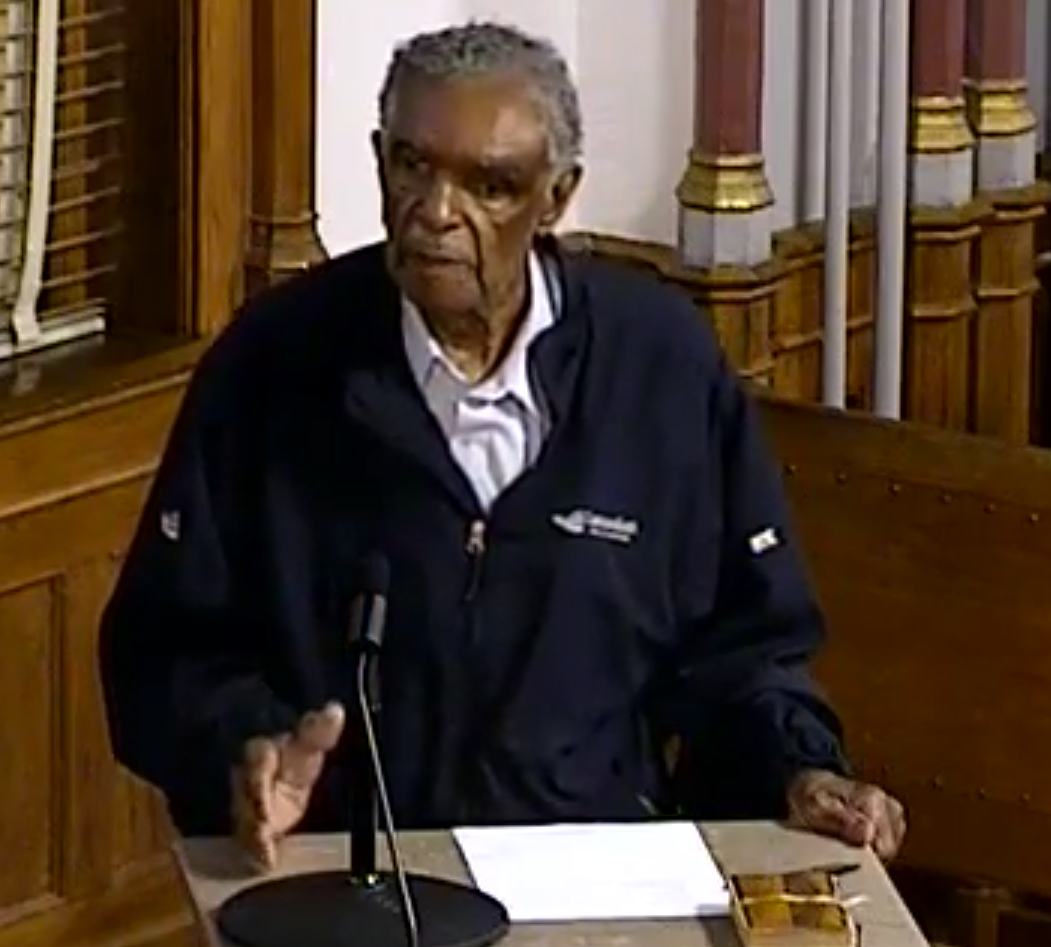

Then there is Johnnie and Ethel Sampson, among New Bern’s most beloved couples.

Johnnie is a county commissioner (in fact, he is running for reelection unopposed). Ethel is a pastor. Their roots in the Duffyfield neighborhood go back so far a street there is named Sampson Street.

Johnnie is a regular at New Bern Board of Aldermen meetings, often providing the opening prayer.

He was there Tuesday, unaware that a property he owns was on the agenda, with staff recommending the former nursing home at 1607 Dillahunt St. be demolished.

According to tax records, the Sampsons bought the building in 1999 for $35,000, three years after Johnnie Sampson was first elected a county commissioner.

The building was once known as Harmony House and is believed to be be the oldest Black-owned rest home in North Carolina. It was scratch-built as a nursing home in 1955, sold in 1960, then sold again in 1999, to the Sampsons.

The old nursing home has been vacant since 1999 and, according to a city staff report, “has been a concern of the New (Bern) Police Department since 2001.”

City Development Services Director Jeff Ruggieri said the roof is torn open, and the city has received complaints from neighbors afraid that their children will be exposed to illegal activity that goes on there.

Ruggieri said in a report that the city has worked with the Sampsons since 2005 until late 2016 trying to get the building secured and the property into compliance with minimum structure codes.

“Ultimately, the owners are unwilling to bring the property into compliance,” Ruggieri said in his report.

But that’s not exactly true. While it is true the city has held numerous meetings with the Sampsons over the years because of concerns about the property, for their part, the Sampsons have taken measures several times in attempts to comply. Still, those attempts were not enough.

Although a letter about Tuesday’s meeting was sent to the Sampsons via certified mail, Johnnie Sampson said he received no notice and was unaware his property was on the Tuesday agenda.

“I just happened to come down tonight,” he said.

Sampson said he has been in bankruptcy for the past two years and wasn’t even sure the Dillahunt property still belongs to him.

Alderman Aster asked Sampson what he would like to do with the property. Sampson said his hands are tied while the bankruptcy is in process.

“I’m just surprised the way the city is trying to take all the property, especially in the Duffyfield area,” he said.

“I tell you, the city is doing some business in our community, they like to take over everything. I’m really disgusted with the city of New Bern doing these things like this. They’ve been slowly taking all the property over there in the Duffyfield area where most of the Blacks live.”

Sampson said city officials were aware he was in bankruptcy and were unhelpful in his effort to determine whether he still owned the property and was responsible for it.

He wasn’t even sure whether he was responsible for cutting the grass there.

Aldermen postponed action on the Sampson property while the city attorney determine who actually owns the property. The last time the city did a title search on the property was in 2015, after all.

For his part, Ruggieri, the city development services director, defended the city’s process.

He said the Dillahunt property has been on the city’s radar since before 1999, but became more formal that year due to vagrant and other illegal activity inside the building.

“The city does not want — ever — to tear down a building in the city. Despite what people say, that’s absolutely not true. We take great lengths, as you can see with this property specifically. Now it started in 1999 and we’re here in 2018. Over and over and over again. Despite other things that have been said tonight, Mr. Sampson was in meetings that we had with the chief building official.

“At the end of the day, everyone is very clear that if those issues aren’t remedied, then the building gets torn down.

“This notion that we are trying to invade Duffyfield is nonsense, and you can see that in this project right here.”

Article by Randy Foster/New Bern Post

Comments and Tips: Contact the Post

Interesting story. Interesting headline.

Not sure this is a “city land grab.” They know these abandoned, derelict houses are more than just an eyesore. Your story shows that w/ the illegal activity allegations from community members and the PD. Not ideal.

Plus, the city likely realizes they will lose money on these properties.

So, what other choice does the city have? Years and years of more “meetings” while the buildings/neighborhood just get worse?

Maybe more events like this